The Origins of Burnout

We entered medicine to serve our patients, but burnout is insidiously creeping into our clinics and hospitals. As one physician described burnout, “what started as important, meaningful, and challenging work becomes unpleasant, unfulfilling, and meaningless. Energy turns to exhaustion, involvement into cynicism and efficacy turns into ineffectiveness.” (Maslach, Schaufeli, and Leiter 2001) Unsurprisingly, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated burnout, with physicians reporting that factors such as persistent lack of control of workload, chaotic environments, challenges with teamwork, and feeling undervalued by organizations as drivers of worsening burnout and even reporting a rise in intent to leave medicine altogether (McClafferty, Hubbard, Foradori, et al. 2022). Anecdotally, we believe burnout has also worsened during surges in pediatric respiratory viral illnesses, the “tripledemic,” as it was coined in the popular media, as pediatricians cared for sick children who overwhelmed capacity at clinics and hospitals (Coughlin et al. 2023). The emotional demands of the work can exhaust our capacity to respond to the needs of our patients (Maslach, Schaufeli, and Leiter 2001), exacerbated by vicarious trauma and compassion fatigue. Furthermore, rates of burnout are higher among physicians who are in residency or fellowship, from minoritized racial and ethnic groups, and who are female (Linzer, Jin, Shah, et al. 2022).

The drivers of burnout in health care are certainly complex, but ultimately tie back to the disconnect between the logistics of the practice of medicine today and what compelled us to enter medicine in the first place. The distance between these two at times seems vast, overwhelming, unnavigable. When we cannot meet the needs of our patients, we feel moral injury; “we perpetrate, bear witness to, or fail to prevent an act that transgresses our deeply held moral beliefs.” (Dean, Talbot, and Dean 2019) When we think about our hardest days, above all, we are fatigued and frustrated by all the factors that we can’t control from within the walls of our clinics and hospitals. We know that many of our patients experience systemic barriers to their health that cannot be solved with a simple prescription or clinic visit. We are anguished when a first grader is injured by a stray bullet, his family desperate to keep him safe in a neighborhood suffering from community violence. We are frustrated when a medically complex teenager continues to have seizures because insurance prior authorization prevents him from getting his anti-seizure medications, unable to access the medicines he so clearly needs. We are devastated when an infant has faltering growth from formula shortages and food insecurity, despite her parents’ every effort to overcome the burdens of poverty to feed her before feeding themselves. We can provide medications and laboratory testing, but our standard practice doesn’t provide gun control, comprehensive insurance, or baby supplies. Burnout is driving that distance between what we can do and what we wish we could do for our patients. It makes us ask, “Am I even helping?” – because ultimately, that is what we seek to do as clinicians. So how can we help? What can we do?

Broad interventions aimed at addressing burnout, ranging from individual to systemic changes, from mindfulness to administrative overhauls, are encouraging and necessary to address the complex and multifaceted drivers of burnout. Professional organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Medical Association are committed to anti-burnout initiatives for their members (Chung 2023; “Measuring and Addressing Physician Burnout” 2024). While we need a comprehensive approach to burnout, with extensive systemic changes, we propose an additional and unexpected antidote to burnout: advocacy. Because, despite the gravity of the issues we face, we are not powerless when we partner with others for a common goal, and together we can tackle these problems that sometimes seem insurmountable.

Turning Problems into Action

Beyond lamenting inequities and avoidable morbidity and mortality, we channel our frustrations into the advocacy work we do, inside and outside of the hospital. Both within our formal job responsibilities as well as with our own time outside of work, we reinvigorate our purpose, regain a sense of control, and begin to heal our moral injury by promoting awareness and action. Advocacy has become core to our identities: we are clinician-advocates, bringing this lens to our clinical, research, and educational work. We encourage our colleagues to consider advocacy as an antidote to burnout, and we’d like to share some of our strategies to effect change.

Gut-wrenching stories like the ones we see far too often require proportionately large societal changes, beyond what an individual clinician can do. Yet, we can, and should, work to address these problems through advocacy. We have taken de-identified stories from our practice and shared them with policy makers, researchers, community organizations, and others. In this way, we have translated social problems that may seem theoretical or abstract to decisionmakers, grounding them in the realities that our patients, families, and communities face. These stories have informed and improved policies at the institutional, city, and state levels, and we continue to work with partners to expand the power and reach of our patients’ experiences (Stewart et al. 2024). As we transform into advocates, we realize that working collaboratively to face systemic problems is empowering. When we partner with others, including most importantly to amplify the voices of patients, families, and others with lived experience, our own morale is improved, and we feel less alone.

We can use research to identify disparities and evaluate policies that affect our patients. Observations in our clinical practice can generate research questions that demonstrate flaws in existing systems or policies. For example, a study on emergency department visits for homelessness (Stewart, Kanak, Gerald, et al. 2018) helped to subsequently change state emergency shelter policy eligibility (Kanak et al. 2023). A study on infant health outcomes among teenage mothers can make the case that educational attainment is associated with infant morbidity and mortality outcomes (Coughlin et al. 2022), providing data supporting programs designed to keep teenage mothers in school.

Many physicians are already engaged in teaching as part of their academic practice. We can build on that expertise to teach trainees and our peers about advocacy topics, strengthening our broader advocacy capacity. A noon conference talk, grand rounds, or academic society platform presentation can easily incorporate information about health disparities or a policy-related call to action. In academia, we can identify gaps in medical education and pursue training that enable us to better advocate for our patients. For example, we recognized that healthcare providers are ill-prepared to recognize and care for patients who were victims of human trafficking, and so we launched an effort to help physicians and other health care providers educate themselves about the medical and social aspects of human trafficking (Coughlin, Greenbaum, and Titchen 2020).

Healthcare systems, not simply individual clinicians, can play a role in addressing social needs, through developing partnerships with community organizations as well as processes in our clinical workflows. We can embed tax preparation services in our clinics to help families claim the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax credit, improving economic mobility and addressing poverty from within our hospital walls (Marcil and Thakrar 2022; “Impact,” n.d.). We can re-imagine federal food assistance programs, co-locating free meal programs with clinical care, improving food security and increasing awareness of resources that exist in the community (Cullen et al. 2019; Plencner, Krager, and Cullen 2022). We can partner with grassroots organizations who serve our communities and know their needs best (“Partner Profile: A Conversation with Dr. Danielle Cullen, MD, MPH, MSHP | Healthcare Improvement Foundation,” n.d.). We can assess for social needs and make appropriate referrals to community organizations and federal programs in our emergency departments (Kanak, Fleegler, Chang, et al. 2023; Messineo, Bouchelle, Strange, et al. 2023).

Since systems change through policy interventions, we use our voices to advocate for children in local and federal government to help shape evidence-based child health policy. To raise awareness of important issues our communities are facing, we write perspective pieces for academic journals (Coughlin et al. 2023), take part in interviews with media outlets (“In Record Numbers, Families without Shelter Are Turning to Massachusetts Emergency Departments,” n.d.), or talk to legislators ourselves. Collaboration between academic pediatricians and institutional offices of government relations, advocacy experts that exist within most institutions to advance policies that improve health, are mutually beneficial and promote health advocacy through policy change (Stewart et al. 2024; Stewart, Lee, Bettenhausen, et al. 2023).

In summary, advocacy simply requires a shifted focus in the clinical, educational, or research work we are already doing, using the expertise we already possess. We are experts in medicine, in the successes and challenges within the healthcare system, and often have a unique window into the strengths and struggles of the communities we care for and are a part of. While pursuing advocacy inevitably requires time, this work reduces the burden of the tragedy and inequity we see and in turn reduces our burnout– to us it is not only well worth the effort, but integral to sustaining a career in healthcare.

Engaging with Advocacy

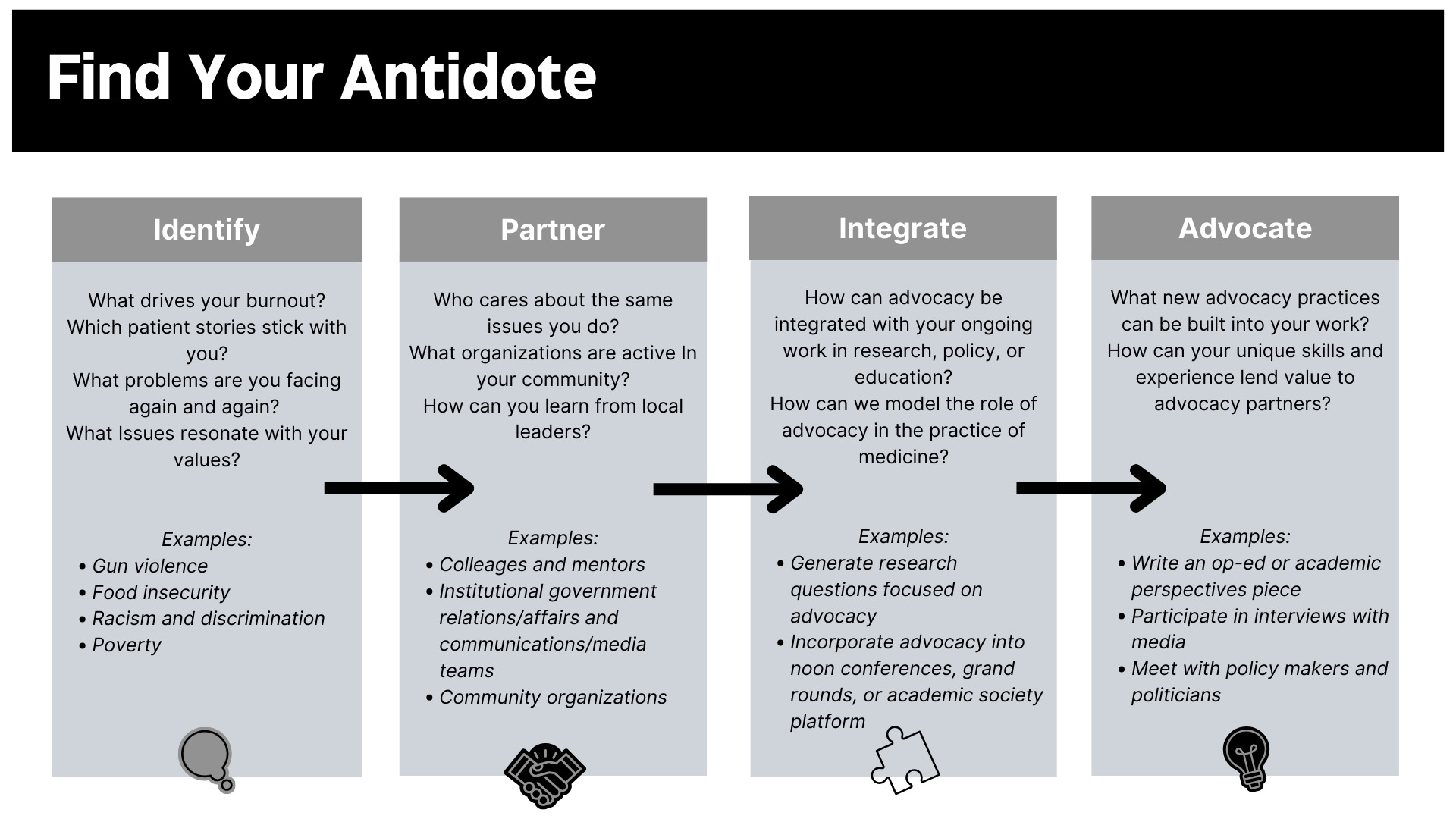

We can’t fix every problem for the individual patients before us, but we can be a part of a larger solution to the systems that affect our patients – and ourselves. As advocates, we are oriented towards solutions that can reduce harm. We feel closer to the issues that speak to our values, healing moral injury. We work in teams with others who care about the same things we do. We help. We feel connected to the heart of medicine again, to our patients again, and to ourselves again. Figure 1 provides some simple steps for identifying your antidote to burnout.

For each of us, advocacy is the lighthouse as we navigate the storms of clinical medicine and academia. It is why we do what we do. Through advocacy, we re-engage the parts of our heart and soul that drew us to medicine, ache when our patients ache, and are inspired to be the best physicians we can.

The onus of burnout rests in the systems in which we care for children – the systems of our communities, our schools, our healthcare institutions, our government, and our country. Those systems need to change in many ways. Advocacy is the antidote that empowers us to transform these systems – for our patients, their families, and, unexpectedly, ourselves.

Declaration of Competing Interests

Drs. Coughlin, Cullen, and Stewart have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) their work.

Author Contributions

Dr. Coughlin conceptualized the piece and drafted the initial manuscript. Drs. Cullen and Stewart critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Funding/Support

There was no funding or support for this project.

Abbreviations

None