Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed a lot for many people, including medical professionals. For some, the politicization of vaccines and COVID therapies (Bolsen and Palm 2022) simply highlighted the role of politics and health policy on health outcomes and patient care. For others, this politicalization was a source of anger and frustration (G. T. Bosslet 2023).

The Good Trouble Coalition (GTC) was formed by a group of healthcare and public health practitioners in 2022 out of this frustration and a desire to turn anger into action. GTC is “a coalition of Hoosier healthcare and public health stakeholders working to improve life in Indiana through statehouse-level advocacy around issues of public health, patient-centered care, and health equity”. (“Hoosier” is the federally designated term for a citizen of Indiana [Indiana State Library 2017].)

GTC was born in 2022 in response to legislative attacks on public health and the patient-doctor relationship and has grown into a nonprofit advocacy group that focuses on statehouse health policy in Indiana.

Here we share who we are, what we have done, and how we have done it in hopes of providing a roadmap for physicians and other health care professionals who are interested in organizing for political advocacy—organizing activities to promote a cause or policy at the regulatory or legislative level to bring about policy change.

Why GTC came about (as told by founding member, Gabriel Bosslet)

GTC was born out of frustration. As an intensive care unit (ICU) physician, I saw firsthand the effects of the pandemic. I watched political leaders downplay public health measures as I was caring for a wave of unvaccinated critically ill patients–many of whom died–in winter 2021. While we were opening new ICU beds in our already-overcrowded hospital, the Indiana General Assembly was debating House Bill 1001, which proposed barring employers, including hospitals, from requiring vaccination of their employees (Indiana General Assembly 2022a).

I testified against the bill in the House Chambers on December 16, 2021 to a packed room of unmasked anti-vaccine activists (G. Bosslet 2021). During the eight hours of testimony, I was one of only two physicians who spoke. I couldn’t understand why there wasn’t an army of us railing against this legislation and started looking for advocacy groups to join in Indiana that did this work (G. T. Bosslet 2023). The Indiana State Medical Association provided the only other physician that spoke against the bill alongside me that day, but they were notably silent on many of the other issues that I thought important.

I ruminated on this through the 2022 Indiana legislative session, which saw bills that allowed for permitless carry of firearms (passed) (Indiana General Assembly 2022c), and in which there was a bill that would have allowed pharmacists to dispense Ivermectin for COVID-19 without a prescription (Indiana General Assembly 2022b) (which did not even get a committee hearing).

And then the leaked Dobbs opinion (Gersten and Ward, n.d.) in early May ignited rumors of a special legislative session that summer to ban abortion in Indiana (Governor Eric Holcomb, n.d.). This was met with relative silence from most of the medical community in Indiana; there was seemingly no coordinated effort to push back on this intrusion into the doctor-patient relationship.

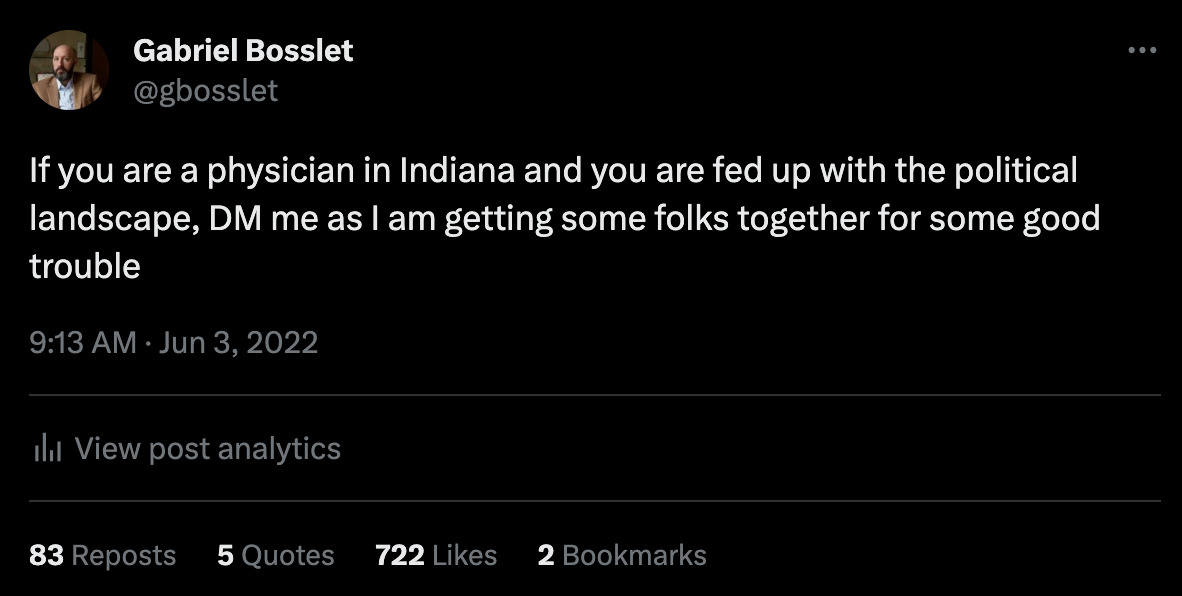

So I tweeted a simple call for healthcare physicians to message me (Figure 1) if they were frustrated about the politics around healthcare in Indiana (@gbosslet 2022). Within hours, 46 people replied to that tweet and 28 people sent me a direct message expressing a desire to turn their anger into action. I was surprised by the response, but it was clear there was a critical mass of individuals eager to engage. Because so many non-physicians also expressed interest, we soon broadened the call to all health care stakeholders. I set up a Google form to collect names, email addresses, and occupations. I shared the form via email and asked others to amplify.

Shortly thereafter, we had a call with about two dozen interested individuals to brainstorm what a group might look like, our scope, and issues about which we could engage. We decided we would center our advocacy around issues of public health, patient-centered care, and health equity. We agreed the focus of our advocacy would be the Indiana Statehouse.

The Good Trouble Coalition was born, taking our name from the late Representative John’s Lewis’ call for advocacy (“@repjohnlewis. Do Not Get Lost in a Sea of Despair. Do Not Become Bitter or Hostile. Be Hopeful, Be Optimistic. Never, Ever Be Afraid to Make Some Noise and Get in Good Trouble, Necessary Trouble. We Will Find a Way to Make a Way out of No Way. #goodtrouble” 2019).

What we have done: Good Trouble’s first act

On July 25, 2022, the Indiana Legislature opened their special session to debate Senate Bill 1 (SB 1), which would effectively ban abortion in Indiana (Indiana General Assembly, n.d.). On the same day, GTC published a full-page open letter in eight newspapers across the state of Indiana (Figure 2). We gathered over 1300 signatures from health care professionals and raised over $20,000 in small-dollar donations to fund the ad buy in six days to encourage lawmakers to preserve access to safe and legal abortion. As our letter stated, “Our medical and ethical responsibility requires that we advise patients about safe and evidence-based medical decisions, including abortion. We call on Governor Holcomb, the Indiana Legislature, and all elected and appointed government officials, to leave medical decision-making to patients and their healthcare practitioners.” (Good Trouble Coalition 2022a) We also rallied at the statehouse.

Our letter was not successful in persuading the General Assembly to preserve access to safe, legal abortion in Indiana, and SB1 passed and was signed into law by the Governor (Indiana General Assembly, n.d.). However, our effort galvanized Hoosier healthcare professionals and public health stakeholders seeking to make their voices heard. It laid bare for many of us the effect of state-level politics on our professional autonomy and on the health and welfare of our patients. Further, in the process of coordinating testimony for the various legislative committees and chambers that would hear the bill, we realized we were filling a niche focusing on general Hoosier health that was not otherwise being filled by existing member-serving, health-focused organizations.

The original critical mass of twelve Good Trouble organizers committed to organizing under this mission:

The Good Trouble Coalition is a grassroots group of Hoosier healthcare and public health stakeholders who collaborate to educate, empower, and facilitate political advocacy to improve life in Indiana in the areas of patient-centered care, public health, and health equity.

We drafted this vision statement to help us enact our mission and guide our policy positions and actions:

To make Indiana one of the healthiest states in the nation by electing science-minded leaders and enacting evidence-based state policies to improve the health and safety of all Hoosiers.

Our mission and vision statements are important north stars for how the board establishes policy positions that we consider priorities for the organization. We feel strongly that evidence should drive public health policy, and that legislators should only involve themselves in individual-level patient decisions when there is a compelling public health reason to do so.

How we did it: The process of organizing

Our public-facing work has garnered attention from local and national outlets including NPR (McCammon 2023), CNN (Stracqualursi, Duster, and Ly 2022) and Mother Jones (Ramchandani 2022). What is not as well-known is the work it took behind the scenes to build an organization. Many of us had experience volunteering for or serving on the boards of nonprofit organizations, but none of us had created an organization from scratch. While we were preparing legislative testimonies, writing op-eds, and showing up for our communities, we were simultaneously figuring out how to formalize and function as a sustainable organization.

Establishing a board of directors was one of our first actions. GTC’s 11 official founding board members evolved from the initial group of organizers. This board represents the group of individuals who contributed to the development of GTC’s mission and helped coordinate initial activities and who wanted to continue being active in advocacy. We were intentional about the multidisciplinary makeup of this group, which represents a cross-section of medical professionals, nonprofit experts, and lawyers. For more information about our individual stories and motivations, see the Supplementary Material. Together, we wrote bylaws, and held the inaugural meeting during which we adopted the bylaws and officially elected our board and officers (Nonprofit Ally, n.d.). Supplementary Table 1 provides a list of founding board members as well as their professional backgrounds.

Our first major decision involved organization type. We knew we needed to be a nonprofit but had to figure out whether to incorporate as a 501(c)3 or 501(c)4 organization (Alliance for Justice, n.d.). This decision would have implications for permissible activities, donation acquisition, and filing requirements. Organizations with similar missions (e.g., IMPACT4HC in Illinois [“IMPACT 4HC,” n.d.]) operate as non-political 501(c)3 nonprofits. However, given the political environment in Indiana, we opted to incorporate as a 501(c)4 social welfare organization, which has more ability to advocate politically. We consulted the National Council of Nonprofit’s general guide (“National Council of Nonprofits,” n.d.-a) (some states have a local association with more specific information) (National Council of Nonprofits, n.d.-b) and the Indiana Secretary of State’s office for guidance on how to incorporate.

Going through the process of incorporation highlighted other structural needs. We needed a mailing address, which meant securing a P.O. Box. Per the criteria for incorporation according to the Indiana Secretary of State’s office, we had to acquire a registered agent—someone who can serve as an official point of contact for communications from the state (McRay, n.d.). We found ours by asking contacts at other local organizations for their recommendations.

All these steps require time, and many also cost money. Much of the initial work of GTC was paid for out of our own pockets, but once we officially incorporated we needed to set up a bank account and establish funding streams. We launched our initial donation campaign in December 2022. The structural implications for this meant we had to find a donations platform that would process payments from donors, deposit in our bank account, and help us track donor activity (we chose Donorbox [“Donorbox,” n.d.] but there are many from which to choose).

We also needed to establish our identity and publicize our work. We created a logo and branding guidelines (luckily one of our board members has a knack for graphic design). We purchased a domain name and built a website. We had officers commit to creating and maintaining social media accounts across various platforms.

Sustaining our work meant acquiring and investing in resources that could help us carry out our mission. For example, we knew we wanted to have access to and presence at the statehouse during the legislative session. After talking to others doing advocacy work, we realized we needed to hire a lobbyist. We interviewed several candidates and chose one who already had a footprint at the statehouse and shared many of our values and legislative interests. We also had to commit to this financial expenditure, which reinforced our need to pursue fundraising. This is just one example of the dual nature of carrying out our mission while simultaneously establishing our organization as a formal, sustainable entity. We summarize some of the necessary steps in Table 1 (many of these steps happened in tandem, rather than sequentially).

GTC’s early accomplishments

Our broad mission translated into many public-facing activities across multiple issues (Figure 3). In our first legislative session (2023), we testified in front of various statehouse committees and full chambers. During that session, we testified in support of pharmacist-prescribed birth control (Tordoff et al. 2022), reorganization and full funding of mental and public health efforts, and against a ban on gender-affirming care (Good Trouble Coalition, n.d.). We issued calls to action to our membership, providing step-by-step instructions, with scripts, on how to contact legislators. We showed up at multiple board meetings to protest the Health and Hospital Corporation’s Supreme Court lawsuit that would have stripped legal Medicaid protections from vulnerable Americans (“IMPACT 4HC,” n.d.). We worked with pro bono legal counsel to submit an amicus brief to the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit opposing the Indiana gender-affirming care bill (“National Council of Nonprofits,” n.d.-a).

We took an active role with the media. We aimed to educate Hoosiers on our key issues by writing op-eds about the abortion ban (National Council of Nonprofits, n.d.-b), the Health and Hospital Corporation lawsuit (McRay, n.d.), and the ban on gender-affirming care (“Donorbox,” n.d.) for the Indy Star. We wrote an opinion piece (“Indiana Business Roadmap,” n.d.) for Stat News, a preeminent health and medicine news outlet, highlighting to our peers the ethical obligation we have to fight for evidence-based public health policies and health equity and did a podcast (https://www.goodtroubleindiana.org/gtc-condemns-ag-attack-11-22) with them. We issued press releases (“Pay.Gov,” n.d.) denouncing the Indiana Attorney General’s relentless attacks on specific medical professionals in our state and the medical profession writ large.

We learned a lot in our initial legislative session. We now update our membership with emails and occasional calls with our lobbyist to keep current on issues during the session. We keep a bill tracker so members can track legislation that GTC is following. Figure 4 provides an example of the spreadsheet we use to track bills available on our website. We meet once weekly via Zoom with our lobbyist to discuss the session and needed tasks and advocacy efforts.

GTC early failures and hard lessons

We entered this work with energy and fervor and quickly discovered that change occurs slowly. This work has been non-linear and fraught with both successes and setbacks.

Notably, we lost significant battles over SEA 1 (Indiana’s abortion ban) and SEA 480 (Indiana’s gender-affirming care ban). Additionally, we found ourselves opposing usual allies on HEA 1426 in 2024, which dealt with access to long-acting reversible contraception for recipients of Medicaid, but excluded intrauterine devices for reasons that were based on ideology rather than science (https://mirrorindy.org/indiana-birth-control-bill-anti-abortion-iuds-implant/). These experiences have taught us that advocacy is a long game, requiring patience, persistence, and the slow building of political alliances.

The risks of advocacy

Engaging in political advocacy as physicians involves several inherent risks that we must carefully navigate to avoid potential professional repercussions. We fully understand that advocating for policies that may not align with the views or interests of our employers can lead to conflicts, professional censure, or even jeopardize our employment. We are mindful of the delicate balance between our personal convictions and professional responsibilities. We work hard to distinguish our personal advocacy efforts from the official stance of our affiliated institutions to mitigate these risks. The formation of GTC has facilitated this, as we can use our Good Trouble titles rather than our professional affiliations in our advocacy work. By understanding these dynamics and taking appropriate precautions, we have been able to effectively advocate for important public health policies while safeguarding our professional standing.

The Future of the Good Trouble Coalition

We like to joke that our organization is run on duct tape and chewing gum, and there is some truth to this. Our monthly board meetings are Mondays at 9 PM because it is the only time a majority of us can get together. Yet, we each care so passionately about these issues, and the importance of voices who use science and evidence to guide decision-making in the policy process, that we make the time.

Good Trouble has evolved greatly over the past two years. Much of our focus has been on fundraising and establishing sustainable funding streams through small-dollar monthly donations and grants in order to fund our legislative consultant, an organization administrator, and a webmaster. We have realized that the struggle for sustenance is not one that will go away—the world of nonprofit survival entails a constant struggle for resources. But we have built something that has passed the two-year mark, and we feel as though we continue to have a meaningful voice in Indiana public health politics. As long as that continues, we will be fighting for science-informed public health policies and health equity in Indiana—long after our current board members are still involved.

Conclusion

For many of us, GTC was our first foray into acknowledging our responsibility to be more politically engaged. We became increasingly aware of the extent to which policy decisions had a direct effect on health outcomes. We also saw how legislation about issues regarding public health measures such as vaccine policy, gun safety, reproductive health, and gender-affirming care were not being discussed with scientific, outcomes-based considerations. Our work with GTC and political advocacy is an attempt to change this.

The pandemic laid bare for many of us that sitting on the sidelines is no longer an option. Public health is inherently political, and being involved in the political process to make things better for the health of us all should be seen as a duty, not something to shy away from. We have had to learn a lot in creating a structure that would have an impact on public health in Indiana and hope that in sharing our story, including the “why, what, and how”, we can help others do the same.

Disclaimer

All opinions are the authors’ own and do not represent those of our employers.

Declaration of Competing Interests

The authors of this manuscript are board members of the nonprofit organization, the Good Trouble Coalition, discussed in the article. They have no conflicts of interest beyond this association.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the work reported in this manuscript. All authors contributed to the conception, writing, and editing of the manuscript and all authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This manuscript had no funding source.

Abbreviations

AG: Attorney General

GTC: The Good Trouble Coalition

HEA: House Enrolled Act

SEA: Senate Enrolled Act

SC: Supreme Court

Acknowledgements

None.