Introduction

Firearm-related violence, accidental injury, and suicide are growing public health crises (Global Burden of Disease Injury 2018). According to Gallup polling data, as of October 2023, 42% of U.S. citizens report having a firearm in the home compared to 37% in October 2019, pre-COVID-19 pandemic (Gallup Polls 2024). It is well established that firearm availability is a strong risk factor for suicide, with firearm owners being 3.67 times more likely to commit suicide than non-owners (Studdert et al., 2020). In 2021, 26,320 firearm suicides and 20,966 firearm homicides occurred in the U.S., which represents 55% of all suicides and 81% of all homicides, respectively. This corresponds to the highest percentage of firearm related homicides in more than 50 years (Simon et al. 2022).

Prevention of firearm violence is essential because more than 95% of victims die within 24 hours of injury (Kellermann et al. 1996). Numerous medical governing bodies have placed emphasis on firearm screening and counseling in the healthcare setting (American Academy of Family Physicians 2018; Dowd et al. 2012; The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2022). Additionally, previous reports have demonstrated the benefits of firearm screening and safety interventions, for example in pediatric (Barkin, Finch, Ip, et al. 2008; Carbone, Clemens, and Ball 2005; Wolk et al. 2017), trauma (Zatzick, Russo, Lord, et al. 2014), and psychiatric (Brent, Baugher, Birmaher, et al. 2000) settings.

Systematic reviews found that having guns in the household increased the risk of homicides and suicides amongst the pediatric population due to access (Johnson, Coyne-Beasley, and Runyan 2004; Miller and Hemenway 1999); while a study of state-level safe storage laws found that such laws decreased unintentional shooting deaths among children under age 15 by 23% (Cummings et al. 1997), highlighting the impact of firearm safety advocacy.

The majority of physicians recognize the importance of firearm injury prevention (up to 84%), yet few actually screen their patients—between 0-3% in direct observational studies (Roszko et al. 2016). This discrepancy may be influenced by several challenges, including limited clinician familiarity with firearms. For instance, one study showed that the majority of Emergency Department (ED) physicians reported little or no experience with handling firearms, despite frequently encountering firearm-related injuries or even weapons carried into the ED (Ketterer et al. 2019). Previous survey data has shown firearms are frequently encountered in the ED, as 20% of ER staff reported guns or knives brought into the ED on a daily or weekly basis, which has a detrimental effect on how safe ER staff perceive their work environment to be (Kansagara et al., 2008). Firearm ownership has also increased since the COVID-19 pandemic, making this a more prevalent current issue (Miller, Zhang, and Azrael 2021). By expanding physicians’ knowledge of firearms during their training, future clinicians may become better equipped and more comfortable with counseling about firearm safety, and their patient families—especially those who have firearms in their home—can become more informed about how to safely store them.

In our review of the literature, there was a paucity of research discussing the development and implementation of firearm safety interventions in the adult primary care setting. We hypothesized that students in a longitudinal primary care clerkship may be particularly well-suited to engage patients in conversations regarding firearm safety due to established rapport, routine follow up, and fewer time constraints compared to other members of the health care team. Through this process, we theorized that students also may gain valuable knowledge about firearm safety as it pertains to the health of patients, enhance their interview skills, and gain a deeper understanding about their role in injury prevention.

METHODS

Educational Process

Overview

Senior medical students created a firearm safety screening and counseling tool, which was integrated into the electronic medical record (EMR) and used during all routine primary care visits. Peer-to-peer training on use of the tool was delivered during structured team huddles before and after clinic under the mentorship of a single faculty preceptor. The target audience included twenty-two medical students and four physician assistant (PA) students who were distributed across levels of training and participated in the same longitudinal primary care clerkship every other week between September 2021 and March 2023.

Objectives

-

Learn the basics of firearm ownership and safety counseling

-

Develop skills in addressing sensitive topics about firearm ownership with patients

-

Improve understanding of safe gun storage and the prevalence of firearm ownership in the patient population

-

Develop and implement a firearm screening intervention that incorporates interprofessional collaboration

-

Provide at-risk patients with cost-free firearm cable locks

Curriculum

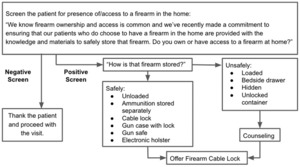

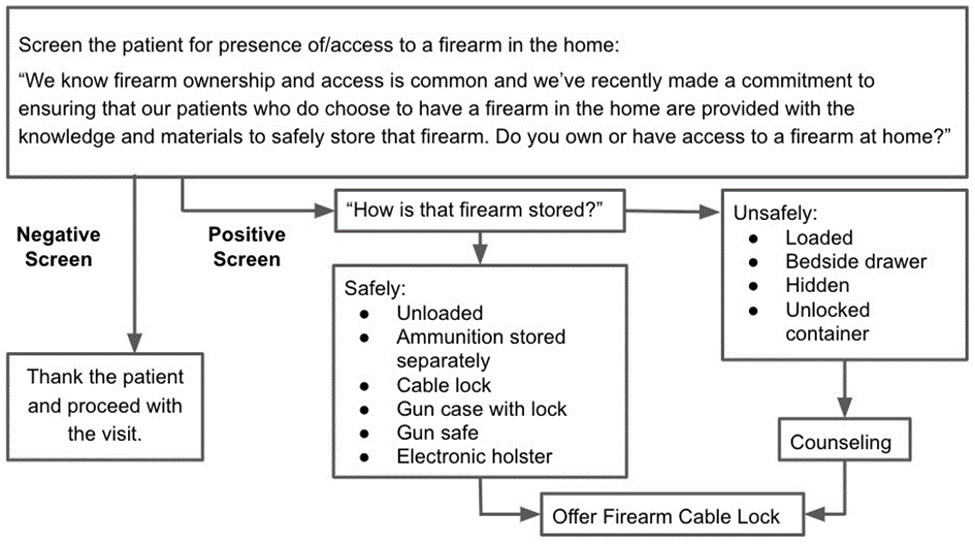

To gain the knowledge sufficient to counsel patients and train other students, four senior students (MA, EJA, ERE, TBG) in the clinic completed the Firearm Violence Reduction Training through Doctors for America (Doctors for America 2021). The senior students collaborated with a community liaison from the Chicago Police Department to learn about established interventions related to firearm violence such as anonymous firearm buy-back programs (https://home.chicagopolice.org/community-policing-group/special-projects/gun-turn-in/) and how to integrate screening initiatives within a student-run clinic. Based on information presented by Doctors for America and the Chicago Police Department, the authors developed a screening tool that was incorporated into the EMR for use during routine primary care clinical encounters (Figure 1). This encouraged universal application of the tool at all routine visits and removed bias in identifying potential firearm owners.

Several resources were used to develop and implement this screening tool. The Firearm Violence Reduction Training through Doctors for America (Doctors for America 2021) informed the screening questions and provided background knowledge on firearm safety. The Epic Systems Corporation EMR was used to incorporate the tool using a SmartPhrase. The screening tool shown in Figure 1 is freely available for adaptation.

This partnership also led to acquisition of donated firearm cable locks for distribution to patients. These are a simple, inexpensive options for safe gun storage and have demonstrated reductions in intentional and unintentional firearm injury (Violano et al. 2018). The locks may be acquired through a number of potential community partners and national initiatives or purchased in bulk from online retailers.

Description of learning environment

The student-run clinic is the site of a longitudinal clerkship that medical and PA students attend every other week throughout the duration of their education (Evans, 2019). Students were distributed across levels of training including first-year/M1 (30.8%), second-year/M2 (15.4%), third-year/M3 (15.4%), and fourth-year/M4 (15.4%) medical students as well as first-year (7.7%) and second-year (7.7%) PA students. Clinic visits were typically conducted by pairs of students at different levels of training, such as an M3/M4/PA2 student paired with an M1/M2/PA1 student. Medical and PA students were paired during each clinic session to foster interprofessional collaboration and promote the exchange of diverse knowledge and experiences. Students were trained by the authors on use of the screening tool as well as basic firearm storage safety during team huddles. To educate their fellow students, the authors shared information gathered from training sessions conducted by Doctors for America and the Chicago Police Department, along with freely accessible online videos that covered safe gun use and the use of gun safety locks. Basics of safe firearm storage included the following criteria: (1) Unloaded firearm; (2) gun unable to be readily accessed via safe, locked case, electronic holster, secured console, or cable lock; (3) Ammunition stored separately from firearm. Students were trained by the authors on how to use the screening tool by walking through how to access the tool in the EMR interface, and how to navigate through the screening questions in line with the flowchart shown in Figure 1. Students were encouraged to preface the firearm screening questions with a statement to help destigmatize gun ownership (Figure 1).

Students also offered firearm cable locks to patients who screened positive for improperly/ unsafely stored firearms. Counseling included motivational interviewing regarding barriers to safe storage options and information on the pros and cons of safe storage options. Students also offered firearm cable locks and basic firearm storage safety information to patients who reported having properly stored firearms. However, there was no measure for assessing whether patients were giving honest responses. After a screening was completed, in-the-moment peer feedback, which was verbal in nature and not collected, was provided as a method of informal student assessment.

Data Collection

From August 2022 to March 2023, students tracked the number of patients screened, patients who reported being firearm owners, patients counseled, and firearm cable locks distributed for future evaluation and analysis. The reason for the medical visit was not tracked as the goal was to integrate the screening in any routine primary care visit. This study was determined to be exempt from Northwestern University Institutional Review Board oversight because the study evaluated clinical curriculum materials and only included anonymous survey procedures.

RESULTS

Patient Outcomes: Screening and Counseling

From August 2022 to March 2023, four students performed 14 firearm screenings. Among those, four patients stated that they had firearms at home, and each of these patients agreed to firearm counseling; two out of four accepted a firearm cable lock.

Student Outcomes

Students who were still in school at the study endpoint of March 2023 (20) were invited to complete a short survey, which included the following questions: “After participating in this project, I have a better understanding of safe firearm storage” (1–5 scale; 1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree); “After participating in this project, I feel more comfortable discussing firearm safety with patients” (1-5 scale); “What was the most valuable content you learned from this initiative?” (optional free response); and “What could be improved in this initiative?” (optional free response). Student survey responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Overall, 65% (13/20) of current students completed the survey. The mean responses for the first two questions were 4.15 ± 0.69 and 4.46 ± 0.78, respectively. A summary of the results by year and program is displayed in Table 1. Students identified the following topics as the most valuable content they learned from the initiative:

“Being comfortable talking with patients about firearm safety”

“Prevalence of firearm ownership among our [clinic] patient population”

“Understanding easy and cheap options for gun safety measures at home”

“How willing individuals are to learn more about firearm safety”

“How to frame firearm safety as a health risk and ask about it in a non-judgmental matter”

“What safe gun storage is in practice and how to approach these conversations with patients. It was also valuable to have a solution to offer like the cable lock, which made the work we’re doing feel more impactful”.

Only one student provided a suggestion for improvement, which was: “more introduction on how to use the locks so we can teach more effectively.”

DISCUSSION

Unintentional firearm-related injuries, which primarily occur in residential settings and are largely due to access to firearms owned by relatives of the victim, continue to pose a major public health issue in the U.S. (Vaishnav, 2023). This is a problem that is likely to increase as firearm ownership expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic (Gallup Polls 2024); thus, as has always been true, the need to advocate for firearm safety is now.

Physicians and trainees have the opportunity and capability to promote patient firearm safety, reduce access to lethal instruments, and potentially prevent fatal injury while maintaining confidentiality and patient trust (Parent 2016). Here, we present one of the first implementation reports of a standardized firearm safety screening used by students to facilitate risk assessment and conversations about safe firearm ownership in a routine primary care setting.

In total, 26 students participated in this initiative for nearly two years, providing ample opportunities to use the screening tool. However, it is worth noting that despite students’ best efforts, screening patients for firearm safety during clinic visits was not always feasible based on clinic scheduling and associated time constraints. Future initiatives could work to build in more dedicated time for firearm safety screenings.

Students came from a variety of educational backgrounds and were distributed across levels of medical or PA training. Having in-the-moment peer feedback fostered a supportive learning environment for students to learn the basics of firearm ownership and how to address sensitive topics with patients. It also provided students with essential practice in giving and receiving feedback and encouraged collaboration between students of different degree programs (Burgess et al. 2020).

To provide feedback on the initiative, students completed a final survey. Survey results demonstrated positive shifts in students’ understanding of safe firearm storage and level of comfort in discussing firearm safety with patients. These results were similar across the different school programs and levels of training. Through free-response survey questions, students voiced that they appreciated the opportunity to gain a better understanding of the components of firearm safety, learn about the prevalence of firearm ownership in the patient population, and provide patients with firearm cable locks. Of note, the initiative was carried out in a relatively small cohort and not all students completed the final survey. Furthermore, this initiative was only carried out in one student-run clinic at Northwestern Medicine with a single clinical preceptor. Thus, future studies will be needed to confirm our findings.

Interestingly, although previous studies on firearm interventions have described concerns about risks to the doctor-patient relationship and patient privacy (Parent 2016), no student in our cohort reported patient hesitancy to disclose firearm ownership status. In fact, one student emphasized that they learned that patients are willing to learn more about firearm safety. Student hesitancy was never reported as a barrier to conducting a firearm screening. Rather, time constraints associated with the clinical schedule were more often an issue. However, it is also important to keep in mind that one limitation of our approach is that we did not explicitly elicit patient feedback regarding hesitancy to disclose information about firearms, making it difficult to know how this was actually experienced. In general, patients expect that physicians will inquire about personal medical topics like sexual activity, substance use, and vaccine status (Parent 2016). The results of the study indicate that firearm ownership can be similarly framed as a potential health risk and screened for successfully.

Every patient who was screened that acknowledged gun ownership accepted firearm counseling and half of them took home a firearm cable lock. The sample size was small, in part due to patient screening outcomes not being recorded in the clinic until August 2022, as such measures were not part of the initial metrics we aimed to record. As initially conceived, the primary purpose of the study was to determine the viability of implementing this screening tool in the student-run clinic and assessing its educational benefit rather than assessing its intrinsic efficacy. Students began recording patient screening outcomes in August 2022 to build upon this current work and facilitate future studies that will follow longitudinal implementation of the screening tool, which may then be used to evaluate the benefit of the screening tool at the community level— number of patients screened, firearm owners, patients counseled, and firearm cable locks distributed—with a larger sample of the clinical population.

There are several opportunities for improvement of this screening tool. For example, one survey response requested more detailed instruction on how to use firearm cable locks. Future studies could consider having all participants complete the Doctors for America training or another formal firearm safety curriculum. It may also be helpful to assess students’ baseline firearm safety knowledge and comfort in screening patients, to better appreciate the effects of the initiative. Future studies may also include other health professional trainees, such as nurse practitioner or physical therapy students, depending on the clinical setting and availability of students. This may further enhance students’ abilities to collaborate with other professionals in their future careers. Finally, future studies could evaluate other ways to promote firearm safety besides safe storage, such as screening for children in the home, concomitant firearm ownership and intimate partner violence or concomitant mental illness, knowledge of protection orders and policies to temporarily remove firearms from a home, among other factors.

Herein, we present the findings from implementing a firearm screening and safety curriculum amongst medical students and PA students in a longitudinal outpatient teaching clinic. Students overall felt more confident in their ability to incorporate a universal firearm screening tool and firearm counseling during patient visits. Further work can expand on the efficacy of the screening tool itself as a firearm safety intervention (i.e., how many gun locks were handed out) as well as incorporate additional elements into the curriculum.

As firearm ownership has increased alongside firearm-related violence, suicide and unintentional injury, the need for initiatives that aim to increase the potential for injury prevention is clear. The call for firearm screening and counseling within the healthcare setting has been made. By using a simple screening tool, more physicians will be able to answer that call and potentially prevent fatal injuries.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Chicago Police Department for providing education on firearm ownership and donating firearm cable locks for distribution in the clinic.

Author Contributions

MA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft. EJA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing.

ERE: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing.

TBG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing.

YY: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing.

DC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing.

VG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing.

FMY: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing.

KLC: Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing.

EE: Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing.

Funding/Support

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

ED: Emergency department

PA: Physician assistant

M1/M2/M3/M4: Medical Student Year 1/2/3/4

Declaration of Competing Interests

The authors declare no relevant financial/competing interests.