Introduction

Vaccines against COVID-19 were developed, tested, manufactured, and, in the U.S., authorized for adult emergency use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in less than a year in 2020. Overall, this vaccine development was a feat of novelty and rapid innovation (Ball 2021) built on a foundation of mRNA research (NIH, n.d.). As of winter 2024, approximately three quarters of adults in the U.S., the setting of focus for this analysis, received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, though only approximately 20% received an updated booster dose as recently as fall of 2023 (KFF 2025). Adults following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance for annual COVID-19 vaccination (Regan, Moulia, Link-Gelles, et al. 2023), or who are immunocompromised and require additional doses as part of a primary series (CDC 2024a), however, may by now have received fourth, fifth, sixth, or more doses of a COVID-19 vaccine.

While COVID-19 vaccines became available quickly for adults and adolescents across the U.S. through emergency use authorization (EUA) granted in late 2020 and mid 2021, respectively (Ali, Berman, Zhou, et al. 2021), it took until the end of October 2021 for EUA of COVID-19 vaccines for children ages 5-11 years (FDA 2021; Walter et al. 2022). In fact, the adult vaccines were fully FDA approved in August 2021, two months before any COVID-19 vaccines were available for kids ages 5-11. Children under age 5 waited a full additional year and a half (Schoch 2021; Anderson, Campbell, Creech, et al. 2021; Kamidani, Rostad, and Anderson 2021; Chen 2022) for vaccine authorization. The first COVID-19 vaccines for children under 5 were only authorized and available in the middle of June 2022 (NIH National Library of Medicine, n.d.; Centers for Disease Control 2022; Fleming-Dutra, Wallace, Moulia, et al. 2022). All the while, these very young children were often in congregate settings like daycare centers and schools, and experienced higher rates of hospitalization and death than any other pediatric age group (CDC 2024).

Disparities in COVID-19 vaccine availability for young children compared with teens and adults raises serious ethical questions. “Standards and requirements for vaccine licensure in the United States are generated and enforced by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration” (Institute of Medicine 1993), and vaccines typically follow an age-deescalation process during trials and licensing (FDA 2018; Harbin, Laventhal, and Navin 2023). Fundamentally, the question is whether the disparities reflect important due diligence regarding pediatric vaccine safety and acceptability in alignment with vaccine research and licensure standards, or if they reflect unjustifiable, avoidable, and unnecessary delays.

In one view, the process of developing pediatric vaccines for COVID-19 followed standard scientific and regulatory protocols. As part of that process, bioethics experts were called on to contribute to discussions regarding pediatric trial inclusion and process (Joffe 2020; Mintz et al. 2021; Harbin, Laventhal, and Navin 2023), including as part of the Operation Warp Speed team (Slaoui and Hepburn 2020), and to raise and assess ethical considerations for vaccination requirements in educational settings (Opel, Diekema, and Ross 2021; Gostin, Salmon, and Larson 2021; Reiss and DiPaolo 2021). Yet, pediatric vaccine access relied on an authorization timeline shaped by formal and informal advocacy from a variety of interests and groups involving values and trade-offs that raise important questions not only about the levers of influence on public health policy decisions, but the potential role of bioethics as an advocacy evaluator and lever.

This paper analyzes the underexplored values and advocacy shaping the COVID-19 vaccine authorization process, and documents the idiosyncratic steps taken in regulating COVID-19 vaccine access for children under 5 years old in the U.S. Ultimately, we suggest that a bioethics lens would help make explicit the reasons, interests, and values underlying the decisions and actions of regulatory bodies in this process.

In conducting our analysis, we employed a philosophical bioethical approach to normatively analyze the values underpinning risk and benefit evaluations informing the pediatric COVID-19 vaccine regulatory process. We identify a role for bioethics in the advocacy domains of community and government, which may cut across individual, adjacent, and structural levels (Earnest et al. 2023). Earnest et al. describe the domain of community as focusing on “the people, institutions, and non-governmental organizations surrounding” a practice “and the patient interests that a practice serves” and can include individuals and institutions like “schools, faith groups and organizations, businesses, and a variety of non-profit and for-profit organizations, associations, and community groups” (209) within a designated locality. Government advocacy may overlap with aspects of the community domain by being interested in similar institutions but focused on the aspect of policy-making within these institutions and at all levels of government (ibid).

In the theoretical model of advocacy that Earnest et al. offer, advocacy can address individual, adjacent, or structural needs: individual is typically at the patient-level, adjacent is acting “on behalf of individuals or groups of individuals with a particular characteristic or need” without producing structural change, while structural advocacy “changes policies, rules, and resources in a permanent way such that the circumstances that impede or impair health are permanently altered” (Ibid., 210).

Such bioethics advocacy across these domains and levels seeks to improve child health and prevent negative health outcomes related to COVID-19 infection, transmission, and hospitalization, and may be applicable to future pediatric vaccine regulation.

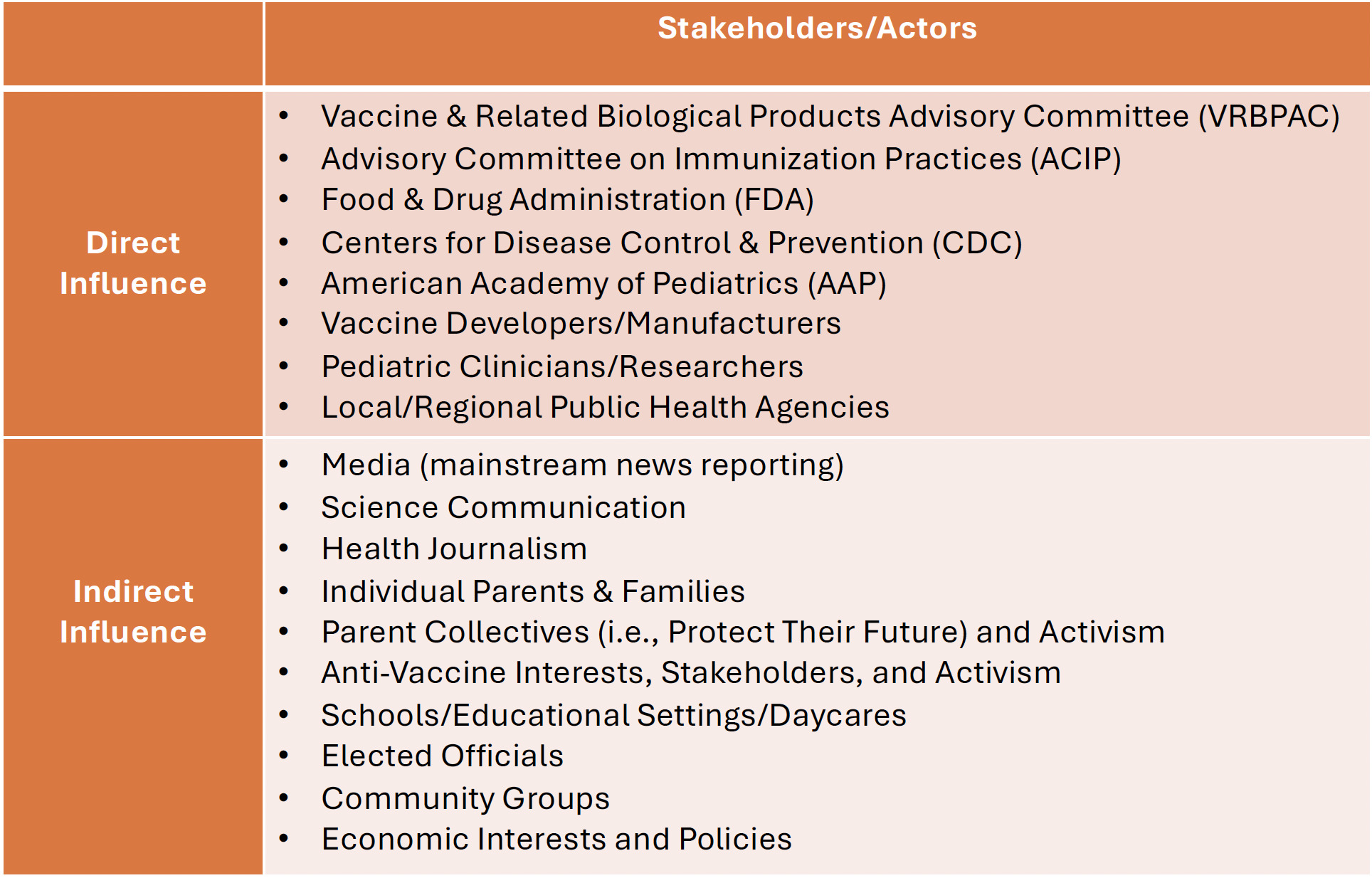

We interrogate how multiple and sometimes competing stakeholders, interests, and values, through direct and indirect advocacy, were able to shape the regulatory and rollout process for COVID-19 vaccines for children between 6 months and 5 years of age in the U.S.

From this we see an untapped role for bioethics, similar to the role bioethicists have played in advocating for ethical and values considerations (Rogers 2019) in other instances of community and government advocacy, such as water crises (e.g., Howell, Doan, and Harbin 2017), regulation of weapon use (e.g., Canadian Academy of Health Sciences 2013), and community dialogues on mental health (St. Vincent’s House and Galveston Island Community Research Advisory Committee 2016).

Timeline and Process

In early 2020, after COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic, scientists and health journalists reporting on the likelihood of vaccine availability against COVID-19 noted that no vaccine against any disease had previously been successfully developed and approved in less than four years (i.e., Mukherjee 2020). Yet, vaccine researchers in the U.S. and abroad responded to the COVID-19 virus by swiftly conceptualizing and designing clinical trials to test novel vaccines, some funded by government programs like Operation Warp Speed (Slaoui and Hepburn 2020; NIH, n.d.) to subsidize innovation.

Vaccine candidates followed the standard processes of development, multiple phases of clinical trials, and review by the FDA to determine authorization or approval, followed by CDC recommendations for their use (FDA 2018; Centers for Disease Control 2022; NIH, n.d.). Ultimately, by the end of 2020, multiple vaccine manufacturers arrived at vaccines that demonstrated safety and efficacy and healthcare workers across the U.S. began having access to those vaccines that December under EUA (Fortner and Schumacher 2021).

COVID-19 vaccines were initially authorized for EUA by the FDA, which has a different set of evidence standards than it does for full approval (granting a biologics licensing application or BLA) (Sherkow et al. 2021). Currently, there are three COVID-19 vaccines available in the U.S. but only two available to young children: the mRNA vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna, respectively; the original formulations of both were confirmed to be highly immunogenic in children under age 5 (Dalapati et al. 2024). To date, neither has been fully approved for children under age 12, although they remain available under EUA and are recommended for everyone ages 6 months and older (CDC 2023). That these remain under EUA but not BLA could have implications for future access of COVID-19 vaccines by children under age 12 years old in the event the EUA is withdrawn, though as long as they remain on the vaccine schedule recommended by the CDC they are currently available and covered by health insurance.

The specific focus of this analysis is on the period from August 2021 through June 2022, beginning with when the Pfizer vaccine for adults received full approval and ending with the emergency use authorization of the first COVID-19 vaccines for children under 5 years old (Figure 1). This was a time of intense direct and indirect advocacy in ways we hope to highlight and analyze here.

Kinds of Actors and Advocacy

Many stakeholders and actors had implicit and explicit roles in contributing to the timeline—either slowing it down or pushing it forward—for pediatric COVID-19 vaccine authorization. This included groups with formal and informal roles in the authorization process (Figure 2). Formalized groups included vaccine developers and clinical trial site leaders, federal agencies like the FDA and CDC, but also the external Vaccine and Related Biologic Product Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) of experts who report to/work for the FDA, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) that makes recommendations to the CDC (CDC 2024b), and pediatric professional bodies like the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) (Chang, Macias, and Dorning 2021).

As loosely structured or unstructured actors with indirect influence on the authorization process, parent groups formed networks and non-profit organizations related to getting kids into clinical trials, advocating for faster vaccine review and authorization (Protect Their Future 2022b, 2022a; Khan 2022), and sharing information about where to access vaccines once authorized. These parent groups and networks expanded around the end of 2021 when further delay in vaccine access for children under 5 years old was announced, tied to the request from FDA for Pfizer to study and report on adding a third dose to the under 5 primary series to further study vaccine immune response prior to reviewing its data collected on the 2-dose series (Mandavilli 2022), and concurrent with a dramatic rise in COVID-19 cases connected to the Omicron wave (Kline and Rosenblum 2022; Bessias, Harbin, and Lanphier 2023).

Informal groups that advocated for transparency and expediency, and against delays in the vaccine trial and authorization process (Physician Coalition Letter to the FDA 2022; Citizen Petition to FDA 2022), overlapped considerably in membership with parent groups who sought information about vaccine trials. Similarly, some of these groups, comprised of parents and pediatricians, advocated for off-label use of the approved adult vaccines for children, which the CDC had prohibited (Lanphier and Fyfe 2021b), or travel to countries like Germany where they were already available (Schreiber 2022).

Loosely organized groups in favor of access to pediatric COVID-19 vaccines existed alongside groups expressing vaccine hesitancy or skepticism, in general and to COVID-19 vaccines specifically. Even the idea of “anti-vax parents” may have played an indirect influence on pediatric vaccination regulation, in terms of regulators’ concerns about the impact that parents’ confusion about the COVID-19 vaccine regulatory process (LaFraniere 2022b) might have on their confidence in other childhood vaccines. Harder to identify were actors who promoted or fueled anti-vaccine views within the policymaking realm, through mainstream or social media, which also permeated official and unofficial discourse during this time period (Howard 2023).

Formal media coverage of kids’ access to COVID-19 vaccines, rare though it was (Bessias, Harbin, and Lanphier 2023), tended to minimize the impact of COVID-19 infection among kids based on early scientific presumptions and evidence (Calarco 2021), either suggesting that infections caused only mild disease in kids and therefore were relatively safe (i.e., as suggested in numerous interviews with economist Emily Oster) (Cartus and Feldman 2022), or that pediatric infections were already widespread and thus provided protective antibodies against further infection such that vaccination was not relevant (particularly once the Omicron wave led to massive numbers of infections concurrent with under 5 vaccine authorization delays (Cancryn 2022)).

Perspectives on the perceived importance, urgency, or risks of pediatric COVID-19 vaccines shared in mainstream or social media, among policymakers (Polis 2022) or other directly and indirectly influencing actors, may not have been shaped merely (or even primarily) by views of clinical safety and efficacy, but interfaced with complex and sometimes competing values and commitments related to public health policy, economic policy, and education and workforce policies, etc. COVID-19 policies in K-12 schools, including school closures and masking requirements, were more examples of the interface between competing values and priorities and the framing (or failure to frame) of them as competing values or priorities. As Cartus and Feldman (2022) analyze, schools provide “important sites of social reproduction, a safety net for children and parents, and public institutions with organized workforces.” In other words, there are interests in student safety, in parents having reliable childcare so that they could return to the workforce, and in school employees having safe working conditions.

But choices to reopen schools and to remove masking requirements were not necessarily framed considering these collective, and sometimes competing, social and material interests. Instead, citing cases where jurisdictions deferred to ‘parents’ choice’ about whether to have their children mask or not (e.g., Perry 2022), Cartus and Feldman note: “When schools dropped masking requirements, supporters appealed to the concept of parents’ choice. But individual choice is a disastrously inadequate framework for addressing collective problems like a respiratory virus. Allowing some people the “choice” to reject COVID safety measures precludes the safety and well-being of others.” A challenge with COVID-19, and perhaps public health policy more broadly, then is how to identify and evaluate the influences and impact of various and at times opaque advocacy interests on what on the surface appeared to be a straightforward scientific and regulatory process in the case of vaccines, or around simplified issues like “parental choice” or minimizing kids’ “learning loss” without identifying, let alone evaluating, competing interests.

A Role for Bioethics

As bioethicists, we are interested in the ways bioethics as a field can participate in advocacy in cases like that of the research, development, and regulation of pediatric COVID-19 vaccines.

Bioethicists can work as advocates themselves based on their specific training and expertise, which often blends a variety of disciplinary backgrounds including medicine, law, theology, and philosophy, among others, with overlapping theoretical and topical knowledge in theoretical and practical bioethics. They can also contribute in their roles as scholars, teachers, researchers and clinical ethics consultants, or media commentators and sources, to highlight different forms of advocacy involved in such processes. For example, bioethicists may help in identifying (often competing) interests, values, and priorities of advocates who may also represent their views directly in the regulatory process through the public comment opportunity available in regulatory meetings, or indirectly by influencing regulator perspectives.

Greg Kaebnick (forthcoming) describes bioethics as a field that “attempts to defend the public’s values” and “develops sets of moral principles and theories that model ‘common morality’” to “guide moral thinking.” Yet Kaebnick also suggests that bioethics, when necessary, engages in “arguing with the public’s values, offering challenges and correctives to it.” Kaebnick suggests “it’s plausible to think of bioethics as aiming both to support and to criticize medicine, the medical research establishment, fundamental biological sciences, and so on.” This work Kaebnick describes, of defending and challenging public and scientific views, is made more complicated by the ways in which there is no singular public or scientific view, and in how they work on or react to each other. Rather than impose a right or wrong view, bioethics has resources to evaluate whether values exist and how they are—and should be—weighed.

Bioethicists contributed to the pediatric COVID-19 vaccine process by researching and publishing on the topic, and at times participating in the regulatory process, as previously described (Joffe 2020; Slaoui and Hepburn 2020; Mintz et al. 2021; Harbin, Laventhal, and Navin 2023). Some offered arguments for and against off-label use of the vaccines approved for use in older populations (Lanphier and Fyfe 2021b; Alpern and Gertner 2020; deSante-Bertkau et al. 2022) and did public outreach on this topic (Persad, Zettler, and Fernadez-Lynch 2021; Lanphier and Fyfe 2021a). Others argued for more careful attention to justifying elements of trial design, including questioning commonly used age-de-escalation approaches to clinical trials (Harbin, Laventhal, and Navin 2023) and successfully advocated for earlier inclusion of pediatric participants in COVID-19 vaccine trials (Joffe 2020) than may have otherwise been the case given typical approaches to age de-escalation in clinical trials (Harbin, Laventhal, and Navin 2023).

Scholarly bioethics efforts did yield potential foundations on which to base advocacy regarding better and worse approaches to pediatric COVID-19 vaccine development, regulation, or administration. Yet, we are also interested in highlighting the role for bioethics beyond the ethics of the regulatory and practice processes. Missing from much of the discourse within the regulatory meetings and the scientific journalism surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine process for young children were conversations about all the actors, interests and values impacting the process, and the ways in which different actors were implicitly if not explicitly engaged in individual or adjacent advocacy regarding its goals, outcome, and priorities. This was particularly relevant to the communication and relational components of advocacy and the skills necessary to achieve it (Earnest et al. 2023) in which communication skills had an impact on the shaping of messages while relationships contributed to building or cohering power among stakeholders through advocacy (which may subsequently inform policy).

While bioethicists were involved in some aspects of these issues as described, they might have played a more significant role than they did, skilled as they are in identifying the multiple agents involved in ethically complex situations, weighing competing concerns within a group, recognizing power imbalances within and between groups, and evaluating the (implicit/explicit) concepts of risks, benefits, and alternatives of clinical and public health interventions. To clearly see some of the roles for bioethicists in this advocacy, we return to the example of the time period from fall 2021 through spring 2022, when the anticipated availability of COVID-19 vaccines for children under 5 was delayed, and Pfizer added a third dose to the primary series for children under 5 years old in its clinical trial at the request of regulators based on initial evidence of immune response to a two-dose series (Mandavilli 2022).

Advocates were concerned not only about the regulatory process itself, which had confirmed safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in every age group over five years of age, but about advocating for access to vaccines for the youngest children, and in doing so, questioning which values were being prioritized by extending clinical trials and delaying authorization. This moment was a catalyst for—and of—many subsequent advocacy efforts. That safety and efficacy had been largely demonstrated was one way that advocacy efforts related to pediatric COVID-19 vaccination departed from previous examples of regulatory-related advocacy. Patient interest groups for diseases like Alzheimer’s, ALS, and HIV/AIDS have at times engaged in regulatory advocacy by calling for access to experimental drugs prior to regulatory review via accelerated approval pathways or expanded access (Lewis-Kraus 2023). In the case of pediatric COVID-19 vaccines, advocates against delayed regulatory review and authorization for children under 5 years were largely seeking access to already approved (in the case of off-label) or already shown to be safe and at least somewhat effective (in the case of advancing authorization) vaccines, based on clinical trials and millions of doses administered in older age groups, including in some cases only slightly older children.

Regarding pediatric COVID-19 vaccines, some bioethicists and public health scholars became involved not only because of scholarly, but also personal and political motivations (i.e., a desire to see their children and communities obtain vaccine access). Some bioethicists or those in adjacent fields addressing bioethical scholarship and advocacy were parents who joined networks of advocates focused on getting infants, toddlers, and preschoolers enrolled in Pfizer and Moderna vaccine trials, across the U.S. and internationally. Some joined conversations about media strategies for publicizing concern about access delays, encouraging journalists to cover this story, and making themselves available for interviews and quotation. Some contacted government representatives. Some helped organize public awareness campaigns and gave public comments at regulatory meetings (FDA 2022; Branswell and Herper 2022). Some evaluated the regulatory discussions and public comments to understand the forms of rhetoric used to insist pediatric vaccine access was not urgent (i.e., Calarco 2021), or that uptake would be low and therefore inconsequential (i.e., Lanphier 2022).

Bioethical methods in applying ethical theory to biomedical topics and skills related to values assessments and the identification and evaluation of a range of risks, benefits, and alternatives are useful for considering the numerous agents involved and the sometimes conflicting or competing interests being prioritized in the unfolding debates about pediatrics COVID-19 vaccine access. One of our suggestions is that bioethicists have a role to play both as formal participants in regulatory committees like VRBPAC, as well as through advocacy, scholarship, and outreach to the public in critical moments of vaccine trial, authorization, rollout, and uptake. While there are clear benefits to having bioethicists in formal roles, it is also beneficial to have bioethicists in roles outside these committees, and able to give critical feedback from without. When vaccine developers and regulatory bodies were noting the need for third dose data from Pfizer on safety and efficacy to have confidence in the vaccine and decided to postpone review of the Moderna formulation to review both vaccines simultaneously, bioethicists could have helped evaluate the conceptions of risk and benefit motivating this decision, were they at the table to do so.

Media attention on the regulatory meetings may have provided the appearance that the vaccine authorization process was simply slowed by lack of sufficient data on safety and efficacy. However, internally within advocacy groups, if not externally as part of the processes or officially commenting on them, bioethicists could emphasize a key point that the process of data collection and interpretation is at every stage value-laden: trials are designed, executed, and evaluated in the context of what scientists, corporations, and regulatory committees understand to be valuable, important, and urgent. While various actors may share the same stated goal to minimize risks and maximize benefits, how to achieve this goal depends on what these actors understand to constitute risks or benefits, as well as their magnitude.

For example, some actors focusing on a health economics evaluation of risks and benefits may take the low total numbers of pediatric hospitalizations to suggest that the costs of mass vaccination relative to avoided hospitalization costs renders pediatric COVID-19 vaccination a low priority. However, actors focusing on a public health evaluation of risks and benefits may prioritize COVID-19 vaccination for young children considering the higher percentage of infants and young children hospitalized for COVID-19 compared to all other age groups besides older adults. On this view, access to pediatric COVID-19 vaccination benefits population health outcomes while minimizing risks of adverse or long-term health impacts in young kids. Bioethicists are trained to identify and evaluate different, and often competing, values and interests as motivators for action in ways that can provide structure and clarity to these different sets of priorities, and evaluations of risks and benefits.

If the risk of COVID-19 infection before vaccination to the youngest children is perceived by the public or framed in the media to be low (or insufficiently understood), this too may deprioritize pediatric vaccine processes. And when vaccines are developed within highly politicized conditions, where anti-vaccination or vaccine hesitant sentiment is one node within a web of many other political commitments prioritizing freedom from governmental authority, political representatives may be cautious about advocating too strongly for vaccines for the youngest children. Understanding how these and other values of economic outcomes, risk, and freedom may coincide and influence the tenor and pace of vaccine development is part of a nuanced evaluation of multifactorial health advocacy, to which an interdisciplinary field like bioethics may be suited.

Although bioethicists may be uniquely positioned to draw attention to conflicting senses of risk underlying data evaluation (with the safety/risk of vaccine products being more discussed than the safety/risk of repeated exposure to the virus), and to the values underlying many public health decisions happening concurrently (e.g., to return to mandatory in-person workplaces, even while doing so requires the youngest, still unvaccinated, children to return to childcare settings), how, where, and when bioethics and bioethicists should be part of these processes remains a hurdle for incorporating this form of expertise.

Bioethicists can highlight the broader social context (e.g., of politicized dynamics of anti-vax sentiment, and its effects on uptake in older pediatric populations) shaping the regulatory process at all levels—but these analyses are not only pertinent to scholarship done in hindsight about the process. Bioethicists might have advocated for greater evidence about the views of vaccine hesitant parents, resisting non-evidence-based speculation about anti-vax sentiments. Relatedly, bioethicists might have publicly and critically examined the FDA’s decision to hold off on authorizing Moderna’s two-dose vaccine until Pfizer’s third dose data was available, highlighting unspoken concerns about anti-vax sentiment being involved in that decision (LaFraniere 2022a). In other words, bioethicists should be part of the processes from clinical trials through regulation and roll-out, at all stages.

Concluding Thoughts: Looking Ahead

Part of our goal in reflecting on the actual and missed role(s) of bioethics in the pediatric COVID-19 vaccine process is to highlight ways in which bioethicists could be better involved in similar future processes. As we have described, the COVID-19 vaccine process for children under 5 years was not only impacted by incomplete science or data collection, and not only by the routine unfolding of regulatory process. It was also influenced by complex layers of diverse interests in and influences on the process represented by multiple stakeholders, directly and indirectly influencing each other, and bringing conflicting values to bear on urgent decisions. Our analysis focuses on the regulatory processes and actors in the US; however, competing values and interests have also led to different pediatric COVID-19 vaccine policies across the globe (see Cameron-Blake, Tatlow, Andretti, et al. 2023), and significant vaccine access inequities, which are outside the scope of this paper but well within the scope of bioethical analysis.

The formal and informal advocacy involved in the regulation of COVID-19 vaccines from the end of 2020 through June 2022 illustrates a necessary but largely untapped role for bioethics to play in clarifying and navigating competing values and priorities raised in complex cases of health advocacy. The advocacy in the context of pediatric COVID-19 vaccine development and authorization is an important and under-explored case which demonstrates not only the significance of health advocacy in an urgent public health situation, but also the ways in which the advocacy work of bioethicists and others can address research and regulatory processes and broader political and public dynamics simultaneously.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Research and Development group at the University of Cincinnati’s Center for Public Engagement with Science and the audience of the paper session on Political and Public Discourse at the 2023 American Society for Bioethics and Humanities conference for valuable feedback on earlier iterations of this paper, and the anonymous reviewers and journal editors who provided feedback on this submission.

Funding/Support

There was no external funding associated with this submission.

Declaration of Competing Interests

Both authors had children under 5 years old during the period this paper analyzes. One author had a child enrolled in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial. These experiences influenced the authors’ scholarly research on ethical considerations regarding pediatric COVID-19 vaccine access.

Author Contributions

Both authors collaborated equally on the initial conceptualization, drafting, and editing of this paper and take full responsibility for its content.