INTRODUCTION

Since 2020, the rates of school shootings, shooting-related youth deaths and injuries, and firearm sales in the U.S. have increased compared with previous years, causing a cascade of collective youth mental health trauma and exacerbating the ongoing youth mental health crisis (Zakopoulos et al. 2022; Hodges et al. 2023; Riehm, Mojtabai, Adams, et al. 2021; Brewer et al. 2022). Since 2020, the number of school shootings with casualties in the U.S. rose sharply from 126 during the 2019–20 school year to 350 in 2021–22, representing a nearly threefold increase (National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), n.d.). Pediatric firearm injuries treated in emergency departments increased by approximately 74%, from 694 pre-pandemic to 1,210 in 2020, with firearm-related death rates among youth nearly doubling during the same period (Carter, Roche, McClafferty, et al. 2022). Simultaneously, firearm sales surged—background checks, often used as a proxy for sales, increased by over 80% in May 2020 compared to May 2019, reaching the highest monthly total since national recordkeeping began in 1998 (Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), n.d.).

Prior reports showed that the majority of U.S. parents and youth were worried about shootings occurring in common places that they frequent, such as schools and day care facilities (Hurst 2022; O’Brien and Taku 2022; Murthy 2021). Strategies to prepare children and adolescents for school shootings, such as active shooter drills, have been shown to be associated with increased fear and hopelessness among youth (Moore-Petinak et al. 2020), while strategies to prevent school shootings and shooting-related deaths and injuries among youth, including secure firearm storage, extreme risk protection orders, community violence intervention programs, and school-based mental health services, have demonstrated reductions in firearm-related incidents and are anticipated to have lasting positive impacts on youth safety and mental health.

Research has also demonstrated that worry about school shootings has been associated with internalizing problems among adolescents, or mental health conditions characterized by inward-directed emotions and behaviors (Hurst 2022; O’Brien and Taku 2022). Although past research has shown connections between youth concern about school shootings and increased mental health symptoms, less is known specifically about how youths’ worry about school shootings, particularly a shooting happening at their school, is associated with their well-being and subclinical mental health symptoms such as stress. In the present study, we aimed to characterize the level of worry about school shootings among Chicago parents and their children, and to better understand how youths’ worry has impacted their own well-being and stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data for this cross-sectional survey were collected from October-November 2022 through the Voices of Child Health in Chicago (VOCHIC) Parent Panel Survey (Supplementary Materials), a triannual survey of Chicago-based parents administered online and telephone in English and Spanish by NORC at the University of Chicago. Parent eligibility criteria included being ≥18 years old, living in Chicago, and being the parent or guardian of at least one child aged 0-17 years living in the same household. Respondents were recruited via emailed invitations generated from probability samples with a response rate of 33.8% (n=598 responses from 1,771 eligible probability-based invitees). To ensure sufficient sample size to permit subgroup analyses, the probability sample was augmented by calibration-weighted, non-probability-based responses obtained through opt-in, online panels (n=531) with further details provided in the Supplementary Materials. Probability-based respondents were compensated $5, and non-probability-based respondents were compensated by the panel to which they belonged. The Institutional Review Boards of Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and NORC at the University of Chicago approved the study. Survey data were anonymized by the survey vendor, the data were stored on a secured network, and access to the data was restricted to the study team.

Survey questions to assess parent and child worry about school shootings were adapted from Pew Research Center surveys (Pew Research Center 2022). To assess parent worry, parents responded to the question, “How worried are you and your child(ren) about the possibility of a shooting happening at your child’s school or daycare?” with response options on a 4-point Likert scale (1 [not at all worried] to 4 [very worried]). To assess child worry, parents responded to the question “How worried are your child(ren)?” with the same response options on a 4-point Likert scale (1 [not at all worried] to 4 [very worried]) on behalf of their children based on their perception of their child’s level of worry about a school shooting happening at their own school or daycare setting. Parents with one or more children between the ages of 12-17 years also reported on their perceptions of their child’s level of well-being and stress for each child in this age range.

Youth well-being was assessed with a modified 5-item World Health Organization well-being scale (Regional Office for Europe WHO 1998). An example item was “My child has felt cheerful and in good spirits,” with response options as follows with corresponding scores: All of the time=5, Most of the time=4, More than half of the time=3, Less than half of the time=2, Some of the time=1, and At no time=0. Responses to the 5-items were averaged to create a composite measure. Youth stress was assessed using a modified 4-item psychological stress experiences scale (NIH PROMIS/ECHO measure) (PROMIS 2024). An example item was “My child has felt stressed,” with response options as follows with corresponding scores: Never=1, Rarely=2, Sometimes=3, Often=4, and Always=5. Responses to the 4-items were standardized and averaged to create a composite measure. Complete survey question and response options are provided in the Supplementary Materials. Parents also answered survey questions on other topics that are outside the scope of this study, including parent beliefs about universal suicide screening, COVID-19 and mental health, and family relationships.

Parents provided demographic information (Table 1). For ease of analysis, parents’ self-reported responses about their race and ethnicity were combined into four groups (non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, Latinx/Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Asian or Other race). Recognizing that race is a social construct (Bryant, Jordan, and Clark 2022), race and ethnicity were assessed and included in the data analyses because firearm violence is inequitably distributed across racial and ethnic categories, therefore we aimed to assess if the mental health impacts of firearm violence are also unevenly distributed across self-reported race and ethnicity groups. Parent education and parent age were each collapsed into three levels, respectively: High school or below, Some college/technical school or College education or higher; ages 18-25 years, 26-45 years, and 46 years and over. Household income was collapsed into three categories based on the federal poverty level (FPL; >=100% FPL, 100-399% FPL, 400%+ FPL) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2023). The FPL for a family of four in 2022 was $27,750; income between 100% and 399% of the FPL corresponded to an annual range of approximately $27,750 to $110,852, while income at or above 400% of the FPL exceeded $111,000 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2023). Full demographic survey items and response options are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

All analyses were population-weighted and performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, North Carolina) with alpha significance level set at p<.05. Chi-squared analysis examined differences in worry about a school shooting by parent-reported demographic characteristics including race and ethnicity, gender, and household income. Mean difference pairwise comparisons examined differences in parent-reported youth stress and well-being at different levels of parent-reported youth worry about a shooting happening at their school or daycare setting. Pairwise deletion was used for missing data.

RESULTS

Survey responses were received from 1,129 parents (10.9% non-Hispanic Asian or Other, 22.7% non-Hispanic Black, 35.4% Latinx/Hispanic, 31.1% non-Hispanic White); see Table 1 for the demographic characteristics of the full sample.

Parent worry about school shootings

Over half of parents reported that they were worried about the possibility of a shooting occurring at their children’s school or daycare (36% very worried, 31% somewhat worried), 22% of parents were not too worried, and 11% of parents were not worried at all. Parent worry differed by parent-reported race and ethnicity: Latinx parents and non-Hispanic Asian and Other-race parents were more likely to be very/somewhat worried (80.8% and 70.0%, respectively) than non-Hispanic Black and White parents (58.0% and 57.4%, respectively, p<.001). Mothers were more likely to be very/somewhat worried than fathers (73.7% vs. 58.4%, p < .001). Parents in the middle-income group (100 to 399% FPL) (Moore-Petinak et al. 2020) were more likely to be very/somewhat worried (72.7%) compared with parents with higher income (59.0%; 400% or higher FPL; p <.001).

Child worry about school shootings

Parents reported lower levels of worry among their children compared to their own worry. Approximately two in five parents reported that their child was worried (19% very worried, 21% somewhat worried), 32% said their children were not too worried, and 28% said their children were not at all worried. Parent-reported youth worry differed by parent race and ethnicity, with over half of Latinx/Hispanic parents reporting that their children were very/somewhat worried about a shooting happening at their school or daycare (54.0%), followed by non-Hispanic Asian or Other-race parents (43.9%), non-Hispanic Black parents (36.1%), and non-Hispanic White parents (26.6%, p<.001). Parents of only older children (11 years and older) were more likely to report that their children were very/somewhat worried about a shooting at their school (47%), compared with parents of only younger children (0–5 years old; 25%, p<.001).

Impact of child worry about a school shooting on child well-being and stress

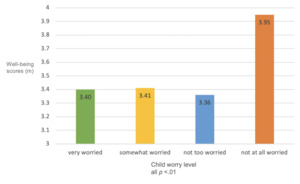

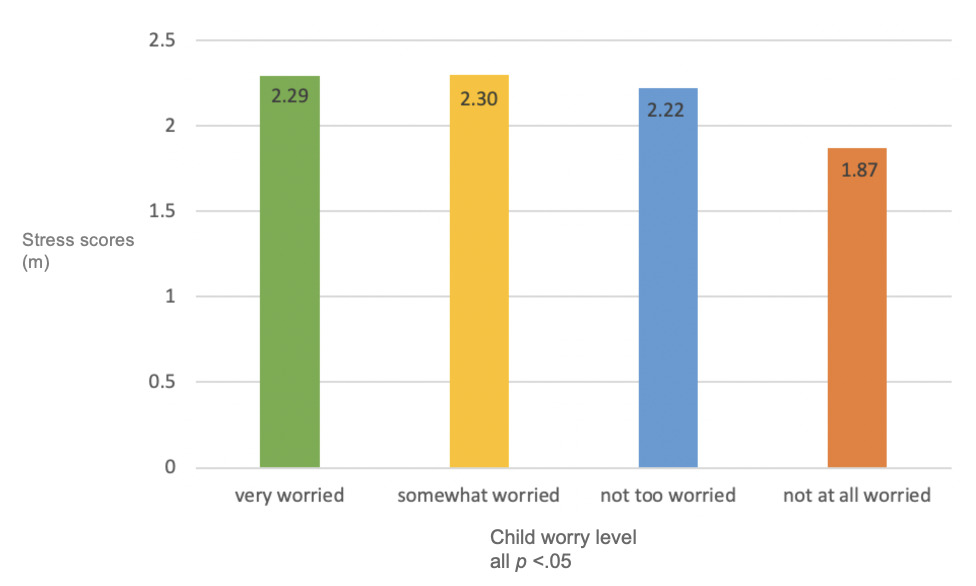

We conducted mean difference tests to compare parent-reported youth scores on well-being and stress across varying levels of parent-reported child worry about school shootings for parents with children aged between 12-17 years old living in the same household. Parent-reported youth well-being scores were lower for youth whose parent reported them to be very worried about school shootings (m=3.40, SE=0.12), somewhat worried (m=3.41, SE=0.13), and not too worried (m=3.36, SE=0.08), compared with youth whose parents reported them to be not at all worried (m=3.95, SE=0.11; all pairwise comparisons p<.01) (Figure 1). Youth stress scores were higher among youth whose parents reported them to be very worried (m=2.29, SE=0.11) and somewhat worried (m= 2.30, SE=0.10) and among those whose parents reported them to be not too worried (m=2.22, SE=0.08) compared with youth whose parents reported them to be not at all worried (m=1.87, SE=0.13; all pairwise comparisons p<.05) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Two-thirds of Chicago parents in our study reported being worried about a school shooting occurring at their child’s school or daycare, consistent with growing concern about school shootings nationally (Graf 2018; Kolko 2016; Nance et al. 2020; Kirkland et al. 2025). Less than half of the parents surveyed in our study reported that their children were worried about a shooting at their school, which is lower than national levels of reported concern among youth and may suggest that the parents we surveyed underestimated their children’s worry about school shootings (Graf 2018). Parent worry and parent-reported child worry varied by several demographic characteristics in this study. For instance, parent-reported worry was higher among families with lower incomes. It was also higher among families with youth who were older, possibly because older youth could have had greater awareness of school shootings from news coverage and through social media. We also found differences in reported parent and child worry by race and ethnicity, with the highest levels of worry reported for Latinx/Hispanic and non-Hispanic Asian or Other race parents and children. Future research would benefit from exploring differences in worry about school shootings by race and ethnicity in more detail to understand whether this potentially reflects a health disparity (Kirkland et al. 2025).

All youth who were reported by their parent as being worried about school shootings had lower well-being and higher stress scores compared with youth who were reported by their parent as not being worried at all. Importantly, the associations between parent-reported youth worry about school shootings and child well-being and stress persisted even among children who were reported to have relatively low levels of worry about school shootings (i.e., "not too worried). This may indicate that even at low levels of worry about school shootings there is a connection between that worry and a child’s social-emotional health. Most notably, in this study any level of worry reported as being greater than “not at all worried” was associated with lower levels of child well-being and higher levels of reported stress.

Our findings must be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. First, the parents in our sample resided in a large urban U.S. city that is affected by gun violence, and as such their worries and their perceptions of their children’s worries about school shootings may differ from those who reside in suburban or rural settings. Despite this, the demographics of Chicago are similar to those for the U.S., strengthening the generalizability of these results to broader populations (Ng et al. 2023). Another potential limitation is that this study surveyed parents about their children’s worry, well-being and stress rather than surveying the children directly; as such, parents’ reports of these variables may not align with how youth would respond to the same questions. It is important to note that parent and caregiver stress can also impact youth well-being, stress, and mental health, as well as parent and caregiver perceptions of these. In the future, it would be beneficial to assess these variables via child report, though it is also possible that asking direct questions about school shootings could be stressful to a child. A final limitation is that these data are cross-sectional, therefore we cannot determine the directionality of the associations identified. For instance, while it is possible that higher levels of worry about school shootings contribute to higher youth stress and lower well-being, it is also possible that youth with higher baseline levels of stress or lower levels of well-being could lead youth to worry more about possible traumatic events like school shootings. Future work could examine this more directly using longitudinal study designs.

Overall, our results demonstrate a high degree of worry about school shootings among parents of school-aged children, and a moderate degree of worry among youth as perceived by their parents. Among youth, even relatively low levels of parent-reported youth worry about a shooting at their school or daycare were associated with negative social-emotional effects, which relates to how children start to understand who they are, what they are feeling and what to expect when interacting with others (Swanson et al. 2015). Parents can support their children by fostering open conversations about fear and grief, validating each other’s emotions, and educating and advocating for mental health resources in schools. Youth and adolescents can support their peers, engage in school safety initiatives, and participate in youth-led advocacy for policies that prioritize their well-being and their communities. Creating strong, compassionate communities and schools where students feel heard and supported can help build resilience in the face of a potential tragedy, but also to potentially prevent one.

Our findings further highlight the ongoing need for federal and state legislative action to prevent school shootings and gun violence. Public policies that restrict firearm access and promote public awareness of the benefits of secure firearm storage can help foster physically safer home and neighborhood environments for youth, and more physically and emotionally safe school environments. This would have indirect benefits for youth mental health, which is of paramount importance in the context of the ongoing youth mental health crisis (Riehm, Mojtabai, Adams, et al. 2021; Lee, Fleegler, Goyal, et al. 2022; ASPE 2023). Parents can serve as effective advocates for safer firearm policies, as demonstrated by organizations like Moms Demand Action (Moms Demand Action 2024) or Everytown (Everytown 2024). Parent advocates can help ensure that safer firearm legislation moves forward to help keep youth safe.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafted and reviewed the work for important intellectual content; provided final approval of the manuscript to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding/Support

This study was supported by an anonymous family foundation dedicated to supporting research that advances community health in low-resource neighborhoods, and the Patrick M. Magoon Institute for Healthy Communities.

Role of Funder/Sponsor

The anonymous family foundation had no role in the design and conduct of the study. Three study team members are members of the Patrick M. Magoon Institute for Healthy Communities.

Abbreviations

ACS, American Community Survey; COVID-19, coronavirus disease of 2019; FPL, Federal poverty level; VOCHIC, Voices of Child Health in Chicago

Data Sharing Statement

Deidentified individual participant data will not be made available.